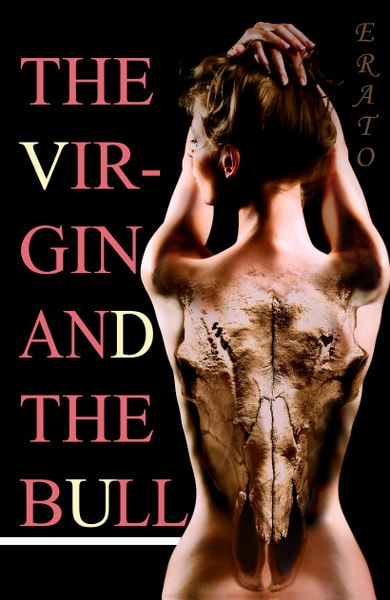

The Virgin and The Bull

Suicide, rape, murder — Love is a serpent more subtle than any of the field.

Twenty-three year old Charles Macgregor had everything going for him, so

why did

he choose to take his own life? As the Sheriff-Depute of Edinburgh

reads through his collected letters, he uncovers a breathtaking story

of femmes fatales, jealous rivals, and love gone violently awry.

An artful and

intellectual thriller told with a noir style, The

Virgin and the Bull shocks

and startles with tense plot, lurid sex and vivid characters amidst a

seductive and scary vision of Old England and Scotland. The frisson

is out of this world when the fiery anatomist Macgregor risks life

and limb to fulfill his desperate desire for the dangerously

beautiful Constance Fawkes, pitted against her mad father and the

more-than-meets-the-eye “virgin” priest, Francis

Exenchester.

is right on point… highly intriguing… It blows your mind.”

Amazon * Google * Smashwords

with ERATO.

author of historical fiction. Her stories are often set in the

Georgian/Regency period, taking the characters past the traditional

bonnets and balls into gritty cities, forced marriages and painful

love affairs.

of Greek mythology: that who ruled love stories. No, it’s not the

same word as erOtic; literally Erato is “the Lovely,” from

Greek erastos “loved, beloved; lovely, charming.” The

author’s own given name being that of a different muse, the name

Erato was chosen as the nomme de plume that seemed especially fit for

writing historical stories with a romantic theme, though she also

writes historical novels without strong romantic elements. Her works

are normally highly researched, subversive, and can tend toward

humorous even when telling of tragedy.

April 28th, 1800.To all my best friends and my dearest family — you could have never done more for me

than all the goodness, favor and friendship which you have offered and provided unto me, your

wretched relation who did so ill-deserve them! You must know that what has passed is, in no

capacity, a mark against you. You cannot be blamed, and you could have offered no help that would

have altered, in any way, the outcome of my unhappy condition. To the unfortunate man who shall

find me, I offer my deepest apologies and regrets that it must be you. As I was a student of

medicine, I know full well the horror that it is to look upon a dead man for the first time, and to see

the human form with frightful lack of motion, heat and soul; but do not fear it; rather, take comfort,

and know that one day this sad fate shall befall each and everyone that you have ever known. Be

familiar with it now, and know what lies ahead for you, rather than to find yourself blindly leapt to the

abyss of death — “And mind, for aw your mickle pride, sae will become o thee.”

With tears in my eyes, I know it is most probably my family that shall ultimately take

possession of this letter, and none but they shall take concern with it. I have loved you all. Never

doubt that I have loved you, but familial love is not enough to sustain a soul that writhes in such

unending torment as mine, all my dreams dead, all hope dispersed. Be not sad for my passing; be

glad that I have ceased to suffer a torment which has been endured for too many months, and which

it is evident shall never pass. If there is a Heaven, perhaps, in spite of this deed, I may still be

admitted thereunto, for this sin has been committed only to prevent a greater misdeed; and in the

name of preserving whatever good may come of this, I beg of you to never disclose my fate to the

one named Constance Fawkes, or now that she is to be married, called Constance Exenchester. If it

comes, ever, that she will ask what has become of me, tell her that I have gone away to India or

Jamaica, or that you know not where I am, but that I am never expected to return. Do not mar the

happiness in her life with any cause to fret herself for me. But if she should pry and insist to know

my fate, or if she might catch a circulating rumor, or by some accident come to know of what has

passed — in a word, if it cannot be helped, and the circumstance be such that denial of the truth

could do nothing more than to concern her the worse, then and only then might you disclose the

facts to her. That you might know those facts, both for your own comfort and for hers, I have

collected here all the artifacts of my time with Constance; in particular my letters to her, which have

been returned by her own hand. How I have suffered in my love for her! And she (though I do not

blame her for this) has chosen another for her spouse, my prior claim to her notwithstanding.

Perhaps I should not have done what was right. Perhaps I ought to have kept her, greedily, for

myself, and compelled her to go forward with a match that would have shamed us both; but I, so

confident in her love, did allow her to slip from my hands, and I shall never see her again. Now I

have lost all; lost unspeakably.

I cannot go on with this writing, with these thoughts, or else I shall lose my resolve and

merely spend another long, sad night wallowing in tears. Having shed such oceans of sorrow

already, one might expect that my bodily humors would be so much disordered that a natural death

could easily come to me; but then, that is a slow and painful process, and I would be at risk that

some well-meaning surgeon might indeed chance upon my cure. Then to what good will I have

prolonged my misery? The time is now. My victory shall be my success in this endeavor — the

accomplishment of my escape. I bid you farewell, my loved ones. I pray that you shall forgive me,

and I am sorry for what I did to Exenchester, and to Fawkes.

Your own, Charles Macgregor.

From the Sheriff-Depute of Edinburgh.

The letter, which you have just read, was found atop a stack of papers which had been

carefully curated, even edited at times, by the late Mr. Macgregor. When discovered, it was rather

soiled from the blood of its own author.

Mr. Macgregor was found dead in his house, in the Cowgate, discovered by his landlord, Mr.

Richards. The blast of the bullet had rendered his corpse a most gruesome sight, such that would

bring terror to the heart of even a skilled medical man as himself. He had shot himself through the

skull, blown so thoroughly asunder that there was nothing left to call a face upon the body. A

butcher’s boy had to be contracted to clean the room after the corpse was taken out, for not even

the lowest housekeeper could be persuaded to suffer the blood, brains and skull that were strewn all

over the floors and wall. Upon further examination, a second, recent gunshot wound was

discovered, through the leftmost side of Macgregor’s hip. Two pistols, emptied of their charges, were

in reach of the body; one of which was found in his hand.

In life, Charles Macgregor had been the sort of man who dressed ever in sad hues, and until

a recent accident, he had been known as a very handsome youth. It is said that many a man would

have been proud to possess such a face, and even his enemies are documented to have called him

“the Scottish Adonis”; yet Macgregor was not previously known to have been caught into this trap of

vanity, and he was perceived to be generally of a sensitive temperament, and much devoted to his

studies. He had ice blue eyes and skin so fair it was described as being like that of a ghost, yet his

colorless complexion was corrected by the vivid hue of his hair, which he wore a little longer than is

the present fashion, but in a styling that suited him well. He stood a height of around five feet, ten

inches. He was said to have always carried in his breast pocket an edition of Fergusson’s Poems.

This was found on his body, with a lock of woman’s hair pressed inside. At the time of his death, he

was aged three and twenty years.

The Macgregors were a family of intellectuals from the

city. Their financial condition saw that they were not altogether lacking in resources; but Charles was

not born into the ranks of society which could have guaranteed his lifelong comfort out of nothing

more than his name or family connections. Thus it fell to Charles to pursue a career. He had sought

to better himself by attending university in England; he received a scholarship at the age of fourteen,

and thrived. He subsequently believed himself to be destined for a career in the high sciences, in

which he should find himself winning his income through patronage and patents. Certainly he was

understood to possess the attention to detail and the depth of mind for such tasks, and nobody ever

claimed that any lack of talent or intellect would hold him back. He was known to have been

committed to his business, and demonstrated skill in his pursuit; and everybody that knew him

expected greatness from this young man. Through means of much private effort, he had been able

to secure for himself a position alongside a most prominent anatomist by the name of Samuel

Fawkes, who dwelt without London. Charles Macgregor did little suspect that this should beget his

downfall; at the time, he considered it only to be a great blessing. He went to the Fawkes home,

where he lived alongside the family: Samuel Fawkes having also in his home a wife, his elderly

mother, a young son, and a daughter of marriageable age who answered to the name of Constance.

These letters are hereby collected and faithfully copied by myself, assistive to the Procurator Fiscal

in his reaching a true ruling on the nature of Mr. Macgregor’s death, and to judge whether he was

killed by his own hand, by some coercive action, or any other cause; for though the letter we found

would appear to suggest he was felo de se, cases have been known in which a murderer did falsify

such documents in order to disguise his own guilt; and the wound to the hip does raise some

concern. Included in these papers are some very intimate details, regarding the lives of Macgregor

and others; my motive in recopying the whole of them is to ensure that nothing shall be subject to

destruction or loss at the request of any relative or acquaintance of the deceased, who might be

disgraced by the revelations within. Only truth and justice are sought from this collection, and it is my

hope that these words shall prove useful to our investigation of the affair. — H. A.