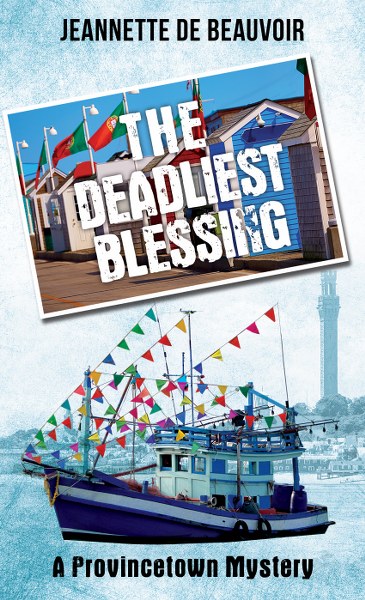

The Deadliest Blessing

body anywhere in Provincetown, wedding consultant Sydney Riley is

going to be the one to find it! The seaside town’s annual

Portuguese Festival is approaching and it looks like smooth sailing

until Sydney’s neighbor decides to have some construction done in

her home—and finds more than she bargained for inside her wall.

balancing her work at the Race Point Inn with an unexpected adventure

that will eventually involve fishermen, gunrunners, a mummified cat,

a family fortune, misplaced heirs, a girl with a mysterious past, and

lots and lots of Portuguese food. The Blessing of the Fleet is

coming up, and unless Sydney can find the key to a decades-old

murder, it might yet come back to haunt everyone in this

otherwise-peaceful fishing village.

Jeannette de Beauvoir grew up in Angers, France, but has lived in the United

States since her twenties. (No, she’s not going to say how long ago

that was!) She spends most of her time inside her own head, which is

great for writing, though possibly not so much for her social life.

When she’s not writing, she’s reading or traveling… to inspire

her writing.

you can see on Amazon, Goodreads, Criminal Element, HomePort Press,

and her author website), de Beauvoir’s work has appeared in 15

countries and has been translated into 12 languages. Midwest Review

called her Martine LeDuc Montréal series “riveting (…)

demonstrating her total mastery of the mystery/suspense genre.” She

is currently writing a Provincetown Theme Week cozy mystery series

featuring female sleuth Sydney Riley.

politics and intrigue of the medieval period have always fascinated

her (and provided her with great storylines!). She coaches and edits

individual writers, teaches writing online and on Cape Cod, and

thinks Aaron Sorkin is a god. Her cat, Beckett, totally disagrees.

Chapter One

The sunset was living up to expectations.

I’d parked my Civic—known affectionately as the Little Green Car—in the row of

vehicles facing Herring Cove Beach, one of the few places on the East Coast where

the sun appears to set into the water. As usual, the light was spectacular. It’s the

light that made Provincetown what it is, the oldest continuously operating art

colony in the United States: the light here, apparently, is like nowhere else.

Or so my friend Mirela tells me. She’s a painter, and is constantly talking about

the light, though when it really comes down to it, she can’t explain exactly what it

is they all see, the artists who live and work here. I know; I’ve asked.

It was late spring, and I didn’t yet have too many weddings crowding my daily

calendar, so I was taking advantage of the calm before the storm of the summer

tourist season really hitting when my spare time, like everybody’s else’s, would

disappear altogether. I’m the wedding coordinator for the Race Point Inn, and

while we do tasteful winter weddings inside the building, the bulk of my work is

in the summertime, as Provincetown is pretty much Destination Wedding

Central, mostly for same-sex couples but really for anyone who wants this kind of

light. The sun was carving a path of gold right up to the beach, glittering and

gilded, and I knew I was smiling, settling back into my seat with a sigh.

My phone rang.

Cell coverage is spotty out here in the Cape Cod National Seashore, and my

experience is that it’s when you really need to reach someone that it’s not going to

happen; on the other hand, when it’s something you don’t want to deal with, the

signal comes through loud and clear. Murphy’s Law, or something along those

lines. I sighed and swiped, my eyes still on the sunset. “Sydney Riley.”

“Sydney, hey, hi, it’s Zack.”

My landlord. This couldn’t be good. I mentally checked the date. Um, I’d paid my

rent this month, right? “Hi, Reg.”

“Hey, hi. Listen, Sydney, I’ve got Mrs. Mattos here and she’s looking for you.”

Of course she was. I live above a nightclub, which makes for reasonable rent with

free Lady Gaga thrown in at one o’clock in the morning; Mrs. Mattos is the

eighty-something widow who owns the very large house directly across the street.

Property developers are probably checking on her health daily as they wait for her

demise; I can’t imagine how many million-dollar condos they could create in that

space.

I take her grocery shopping to the Stop & Shop once a week and I’ve noticed,

lately, that she’s finding more and more excuses to come over and buzz my

doorbell. She’s lonely and probably a little scared and most of the time I try to

help, but the silly season was already upon us and there was a lot less of my time

available. Generally I try to wean her off daily visits by May, but we were already

into the beginning of June now, and she was crossing the street rather than

calling, a sure sign of distress.

Mrs. Mattos is frequently distressed.

Still, it must have been something out of the ordinary for her to have buzzed

Zack, who owns the nightclub as well as the building and was probably peeled

away from his never-ending paperwork to talk to her. Mrs. Mattos is usually a

little nonplussed around Zack, who regularly paints his fingernails chartreuse or

purple, and owns an extensive assortment of wigs. “She’s there with you now?”

A murmur of conversation, then Mrs. Mattos’ quavering voice on the line. “I just

need you to come over, Sydney,” she said.

The sun was dipping into the water now; the show would soon be finished. Above

it, scarlet and pink streaked across the sky. Some day, I told myself, I was going

to be old and quavering, too. “Okay, you go back home,” I said. “I’ll be there in

twenty minutes.”

Her name is Emilia Mattos, she stands about five-feet nothing and might weigh a

hundred pounds. But every bit of her, like most of the Portuguese women in

town, is muscle and sinew. I know her first name, but I’ve never used it; there’s a

certain distance, a certain decorum the elderly Provincetown widows observe,

and I respect that. Out on Fisherman’s Wharf there’s a collection of large-scale

photographs of elderly Portuguese wives and mothers, an art installation called

They Also Face The Sea; Mrs. Mattos isn’t one of them, but she could well be.

Back when Provincetown was one of the major whaling ports, ships stopped off in

the Azores to take on additional crew, and a lot of those people settled back in

town and sent for their families; by the end of the 1800s they were as numerous

as the original English settlers. Nowadays there are fewer and fewer Portuguese

enclaves, as gentrification switches into high gear and Provincetown’s fishing

fleet dwindles; but the names are still here: Mattos, Avellar, Cabral, Gouveia,

Silva, Amaral, Rego, Del Deo.

Up until about ten years go, a prominent advertisement in the booklet for the

Portuguese Festival was for the small Azores Express airline, when there was still

a generation in town that was from Portugal itself; you don’t see that anymore.

She was standing in her doorway when I found a parking place for the Little

Green Car and got to our street. I’ve read in books about people twisting their

hands; I’d never actually seen it until then. “Mrs. Mattos! Are you all right?

What’s wrong?”

“Probably nothing,” she said, on that same quavering note. “Oh, I’m probably

disturbing you for nothing, Sydney.”

“Not at all,” I said firmly, taking hold of her elbow and turning her around. “Let’s

go in, and you can tell me all about it.”

She was docile, letting me steer her back in the house and into the big kitchen

where most of her life seems to take place. She has a home health aide who comes

in to help her with bathing and laundry, but she doesn’t let anyone touch her

stove: not to cook, not to clean. And when I say clean, I mean clean within an

inch of its life: everything in Mrs. Mattos’ kitchen gleams. Not for the first time, I

lamented that she couldn’t make it up my stairs: if she expended about an eighth

of her usual zeal, my apartment would be cleaner than it had ever been.

She sat down, still fussing with her hands. “I’m having construction work done,”

she said, and stood up again. “I should show you.”

“What kind of work?”

“Insulation.” Her voice was repressive, as if she were delivering censure of

something. We’d just come off an amazingly, spectacularly cold winter, with

single-digit temperatures and a nor-easter that brought the highest tides ever

recorded, so I suspected she wasn’t the only one thinking about making changes.

“In the walls. Them people at the Cape Cod Energy said I should.”

“Okay.” I still wasn’t getting what was wrong here. “Do you want to show me?”

She turned and led me into the front parlor (in Mrs. Mattos’ house, you don’t call

it a living room); I had to duck to get through the heavy framed doorway, and the

ceiling here was about an inch or so over my head. She, of course, had no such

problems. A loveseat had been pulled away from one of the exterior walls and a

significant hole made. She didn’t have drywall, but rather plaster and lathing, as

older houses tended to. “There wasn’t nothing wrong with it. The insulation

before was just fine,” she said, resentful. “Seaweed.”

“Seaweed?”

She nodded vigorously. “Dried out. It’s what they used.” No need for anything

else, her tone suggested.

“Okay,” I said again. “What is—“

“Go look,” she said, flapping her hands at me. “Just look.”

I looked. I pulled my smartphone out of my pocket and used the built-in

flashlight. Wedged between strips of lathing was a box. “Is this it?”

Mrs. Mattos blessed herself. “Holy Mother of God,” she said, which I took for

assent.

“Can I take it out?” I asked, eyeing the box. It looked as innocuous as last year’s

Christmas present. Well, maybe not last year’s. Maybe from sometime around

1950.

Another quick sign of the cross. “Just don’t make me look. I can’t look again.”

I put my smartphone in my pocket and reached gingerly into the opening. Didn’t

Poe write a story about a cat getting walled up somewhere? “Who’s doing your

work for you, Mrs. Mattos?” It didn’t look as though they’d gotten very far in

opening up the wall.

She was back to twisting her hands again. “The company wanted so much,” she

began, and I nodded. Rather than getting a contractor, pulling a permit, having a

bunch of workmen in her house and paying reasonable rates, she’d found

someone to do it on the side. Someone’s unemployed cousin or nephew,

probably. That sort of thing happens a lot in P’town, especially among the thrifty

Portuguese. It explained the size of the hole, anyway: this was someone without a

whole range of tools.

I pulled the box out—it was about the size of a shoebox, only square—and set it

down carefully on the coffee table. Mrs. Mattos was looking at it as though

something were about to pop out and bite her, like the creatures in Alien; she

actually took a physical step back. This wasn’t just Mrs. Mattos being Mrs.

Mattos; this thing was really spooking her.

I sat down beside the table and gingerly—you can’t say that I don’t pick up on a

mood—lifted the top off the box. Sudden thoughts of Pandora blew by like an

errant wind and I shook them off and looked inside.

Shoes; small shoes. Children’s shoes. Three of them, and none matching the

others. It was wildly anticlimactic. “Shoes?” I said, doubt—and no doubt

disappointment—in my voice.

“It’s not the shoes,” she said. “It’s that we shouldn’t never have moved them.”

I looked at them again. Old leather, dry and curling and peeling. But shoes? She

was clearly seeing something I wasn’t. Had these children died some horrible

death? Were these memories of lives that hadn’t been lived to their fullest?

Something haunting, a song or an echo of laughter, moved through my mind as

though on a whisper of summer air. I didn’t recognize the tune. “Mrs. Mattos?”

“It’s to keep them witches out,” she said, grimly.

“Witches?”

She nodded. “An’ now there’s nothing to keep ’em from coming in. And nothing

we can do about it, neither.”

I enjoyed getting to know your book and thanks for the chance to win 🙂

This looks like a good read. Thanks for the giveaway!