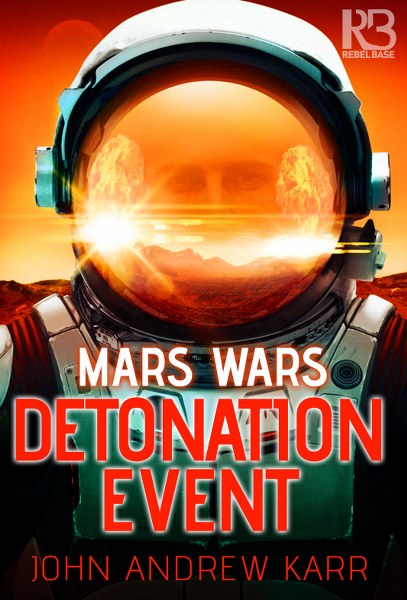

Prologue

2228 AD

The abyss and its twin gape at the Martian sky as if aware of the pain to come.

One in daylight, the other night, they disrupt a global desert. The tunnels thrust to the very heart of the

planet, as if the God of War had twice speared his namesake and wrought its demise. Mars was never a

kind deity, and while he is no longer capable of violence, his blood-colored world remains just as hostile

to life.

Here the sun rises and sets without mortality to mark the passage of time. The thin air constricts no

lungs. The cold bites neither flesh nor frond. Beds of ancient waterways gather dust, indistinguishable

from surrounding barrens. Volcanoes stand as slowly withering ghosts. The underground reservoirs that

once supplied them with magma cooled to rock millennia ago. Deeper still, the once-molten outer core

endured the same fate, entombing the mass of solid iron, nickel, and sulfur that had been its heat

source: the radioactive inner core. Both are cold now, and there is no geologic activity throughout the

entire planet.

Mars orbits the sun—half again beyond Earth’s orbit—as a rocky corpse.

But perhaps not eternally doomed.

The tunnels are the first phase of a mission where the odds are seemingly light years long and without

historical precedent. Even if the mission is initially successful, the duration is unknown. Something killed

Mars before and can do it again. But a chance at life has arrived where there was none. An opportunity

to restore the vibrancy of the planet’s youth, now only hinted at with subterranean ice and mysterious

impressions upon the withered husk of the surface.

In its first billion years, the red planet may not have appeared red at all, but purple or even blue like

Earth, depending on the ratio of breathable air to iron oxide particles spewed from volcanoes and lifted

by wind from mountains and deserts. Surface water existed in the form of streams and lakes and

perhaps even seas. Clouds of water vapor circled the globe. Lightning flashed and thunder boomed.

Rain fell on Mars.

And it was no coincidence that the planetary cores were active and “alive.”

Radioactive heat loss and convective currents of magma produced a magnetic field that bound the

atmosphere to the planet in a geologic dynamo, the like of which still functions on Earth.

What killed Mars?

Perhaps its smaller size limited the amount of radioactive supply, and it simply ran out of energy. Or

massive impact with an asteroid ejected the charged particles out to space. Whatever the case, death

arrived soon after the Martian inner core went cold. Having lost its heat source, the molten outer core

turned to stone as if succumbing to the Hydra’s gaze. The dynamo failed and its magnetism all but

vanished. Gravity alone was too weak to hold the atmosphere. Air and water molecules escaped into

space. Without a magnetic shield and atmosphere to deflect them, solar winds and radiation further

stripped the surface dry.

Mars lost the means to support life beyond a microbial level.

Now temperature fluctuations spawn the only weather events. Night and polar regions regularly plunge

two hundred degrees below zero Fahrenheit; cold enough to freeze its most abundant gas—carbon

dioxide—into dry ice, though at times the equator at full sun can reach as high as sixty degrees. Far less

drastic temperature swings combine with the weak gravity in a near vacuum to spawn frequent dust

storms. The greater the temperature difference, the larger the storm.

Dust, prevalent everywhere, is lifted rather than scoured from the surface. Storms of it can be

monstrous, at times engulfing the entire planet except for the gargantuan Olympus Mons. Far more

common are the dust devils that waltz through a desolate Hell.

Some of the rust-hued particles fall into the open maws and down the tunnels.

No twists or turns arrest their journey. They gain no purchase along laser-bonded walls. Down they drift

like mineral snowfall, passing signal relays at every mile. The dust falls for weeks toward the core.

Recent inductees will never reach bottom before Detonation Event.

Electronic relays form a spiral pattern and flash in sequence for two thousand miles, down and back

again, each briefly illuminating a section of tunnel along the way. Constantly monitored by satellites

positioned above, the relays are members of a large supporting cast.

The lead roles belong to the hydrogen (thermonuclear) megabombs residing at the base of the each

tunnel. These are cutting-edge nuclear fusion explosives; the latest in the class of Asteroid Busters.

Ever silent, Mars awaits its chance at resurrection.